Diegetic & Non-Diegetic ElementsNarrative films include elements that are part of the story-world, such as the setting, characters, and so on. This is collectively known as the

diegesis. The elements that make up the diegesis are referred to as the

diegetic elements or

digetic devices. Elements that are not part of the actual story, for example the musical score or the opening and closing credits are

non-diegetic elements / devices. They all, however, form part of the overall storytelling, i.e. the

narrative. Therefore, narrative elements include both diegetic and non-diegetic elements.

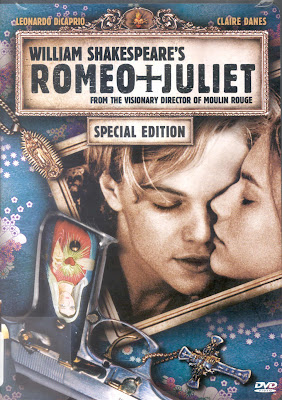

Story (Fabula) and Plot (Syuzhet)When we speak of “narrative” we usually mean “story.” A

story is a series of events that are recounted (i.e. described or narrated) in their

chronological order. However, if you know anything about stories, you will know that story events are not always told in chronological order. There is a difference between a narrative’s story (the chronological events, also known as the

fabula) and its

plot. The latter is the events of the story, which have been

rearranged in a creative way to enhance the story. In the plot, also known as the

syuzhet, the story events are not always in a chronological sequence. Past events may be shown (

flashbacks) or future events (

flashforwards) may be narrated early in the the story telling. Many well known narratives do not commence at the beginning of the story – some actually start at the end, for instance the films

Citizen Kane (1941) and

Momento (2001).

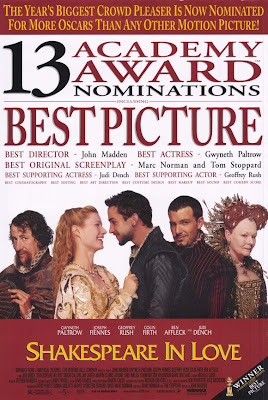

Narrative StructureThe narrative structure of a classical drama, like the Shakespearean play, can be depicted by the following illustration, known as

Freytag’s pyramid.

Act One

Act One: The narrative starts with an

exposition which provides the background information and introduces the characters (protagonists and antagonists), the setting and also the basic conflict and an inciting moment. The inciting moment is what causes the protagonist to act.

Act Two: This leads to a

rising action; the conflict becomes clearer as the story progresses.

Act Three: Eventually there is the

climax. The climax is where a big change in the story occurs, also known as the

turning point. Things will either go well or bad for the protagonist.

Act Four: Next is the action starts to wane (

falling action) as the conflict between the protagonist and the antagonist unravels.

Act Five: Finally there is a resolution – a dénouement (happy conclusion) or a tragic ending.

The typical narrative film follows a similar structure, but instead of the five act structure it is condensed into only

three acts.

Act One contains the

exposition and turning point.

Act Two includes the

complications that lead to the

climax. Lastly, in the

third act the

action falls and the story comes to some

resolution.

Another interpretation by

Kristin Thompson is that contemporary narrative follows a

four-act structure, rather than a three-act structure, in which the

first act contains the

exposition and a first turning point, in the second act the action leads up to the

major turning point, in the third act the struggle continues toward the goal or

climax, and finally in the fourth act the story comes to a

resolution, known as the epilogue.

When describing the plot of a film it is useful to keep these narratives structures in mind to help you organize the narrative in a coherent manner.

While the three-act or four-act narrative structures are common, they are not the only narrative structures. To understand other types of narrative structures, we need to understand narrative layers.

Narrative LayersA single narrative layer is one level at which the story occurs. However, it is possible to have another story occurring within the main story – for instance, the characters in the main story could be telling another story (maybe even reading a bedtime story), and so we have a story within a story. In other words, there are two diegesis or two layers, the one embedded in the other. In theory any amount of narrative layers are possible. The first narrative layer is often referred to as the “

frame narration” in film theory.

Some Variation on Narrative StructureNarrative structures usually have a clear and expected flow of events. A protagonist faces a problem (antagonist) or goal, strives to overcome or achieve it, a climax results after which the protagonist has overcome the problem or achieved the goal, or where the protagonist fails (in which case it is called a tragedy). But in the end, there is a resolution. In other words, the audience understands that the story has ended – there is

closure. Traditional narratives are also clear, the audience easily understands the space, time, and events; there is also unity between the causes and effects; the characters are identifiable and their motivations understandable; and the focus is on the diegesis.

Some narratives are not so clearly defined. A number of narratives may seem to lack a clear problem or goal for the protagonist to overcome or achieve – these are called

episodic narratives. Other narratives may be

open ended, i.e. there is no resolution and the audience is left unsure whether the protagonist has achieved the goal, or overcome the problem – there may still be unanswered questions, or unresolved conflicts. The narrative may also depart from traditional conventions: it may lack clarity with conflicting storylines and space, time and events that are difficult to understand; there may be a lack of unity where the law of cause and effect is not upheld; characters’ goals and motivations are unclear, or they may be too far removed from “normal people” that the audience cannot identify with them; and there is an intrusive focus on the non-diegetic elements, like addressing the audience directly, or revealing cinematic “tools”, for instance showing the cameras.

NarrationIn books it is much easier to identify the narrator, i.e. the person that is telling the story (i.e. the speaker). In literature there are also different words used to describe different types of narrations; for instance, it could be a first person narration (one of the characters is telling the story from his own point of few), a third-person narration (the story is not told by one of the characters), or in some cases even an omniscient narration (the narrator knows everything about everyone).

In film, it is much more difficult to identify the narrator. Usually there is no audible narrator – instead we only get to “see” what the cameras see. What the director (or cinematographer) chooses for us to see, is in effect part of the telling of the story – part of the narration of film. Sometimes the camera shows what one of the characters are seeing, as if we were seeing the world through the eyes of that character. This is known as a

point-of-view shot, when the audience shares the visual perspective of a character. We will look at different ways of using the camera later in the course.

Apart from the camera giving us a visual interpretation of the diegetic world, there are also other narrative elements that contributes to the story telling, like sound, mise en scène, cinematography and editing. We already discussed sound and will discuss the other elements later.