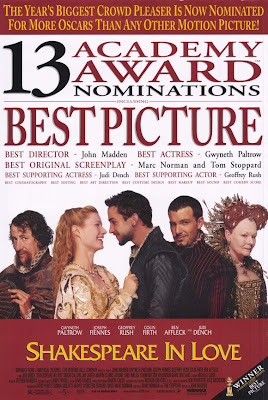

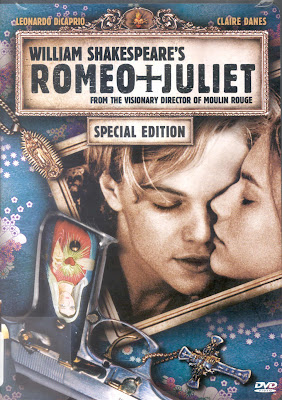

Your final paper grade will go towards your final exam grade. For your research paper you need to discuss one film in detail. You may choose any of the following films: Romeo & Juliet (1968), Romeo + Juliet (1996), West Side Story (1961), Shakespeare in Love (1998), Hamlet (1948), Hamlet (1996), Hamlet (2000), Richard III (1995), The Lion King (1994), Henry V (1999), A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1999), Forbidden Planet (1956), or Ran (1985).

Your paper should contain the five sections following:

1. Introduction

The introduction should include all appropriate metadata and a short review of the film. The introduction should further outline what you will do in the rest of the paper.

2. Narrative Form

In this section you will do a full explanation of the narrative structure of the film.

You will divide the film into three, four, or five acts, depending on the film. Films that are based on Shakespeare plays and which follows the play closely will use the Five Act Structure (according to Freytag’s Pyramid). Other films will fit either within the Three Act Structure or Kristin Thompson’s Four Act Structure. You need to choose the narrative structure that best fits the film you have chosen.

Furthermore, each Act is made up of different scenes. You have to identify the different scenes and provide a précis for each.

As part of the Narrative Form you need to discuss the different aspects of each Act, indicating, for instance, the exposition, the rising action, the turning points, the climax, and the resolution.

You will conclude this section by giving a summary of the film’s plot, making reference to both the fibula and syuzhet where appropriate. You could also mention relevant Cinematic Narrative Elements like Parallels, Allusions, and Motifs if appropriate.

3. Scene Analysis (Scene Exposition)

For your research paper you have to do an exposition of one scene. An exposition is a detailed description. To do this exposition you have to describe the Mise en Scène, Cinematography, Editing and the use of Sound in the scene. To do it thoroughly break the scene up into all the “takes” (individual camera shots) that constitutes the scene and describe each. The analysis may also include any relevant Cinematic Narrative Motifs.

4. Film Analysis

Finally you need to write an essay that discusses some elements in film, like certain motifs, or certain aspects of the Mise en Scène, Cinematography, Editing or the use of Sound that the filmmaker used to convey a specific idea or message.

[When choosing the scene for your Scene Exposition (Section 3), it is wise to choose a scene that will illustrate some of the points you want to make for your Film Analysis in this section (Section 4).]

5. Conclusion

Conclude your paper by summarising what you have done and giving a more thorough review of the film.

Wednesday, May 26, 2010

Monday, May 17, 2010

Cinematography

The following points were discussed in class. Make sure that you are able to identify and / or describe each one of these different cinematographic techniques.

1 Time

1.1 The Shot & Scene

A shot is a series of uninterrupted frames. Several shots edited together forms one scene. Every scene is a coherent narrative with a beginning, middle and end.

1.2 Altering Time

1.3 Accelerating & Freezing Time

2 Camera & Space

2.1 Camera Height

2.2 Camera Angle

2.3 Camera Distance

2.4 Camera Move: Exploring Space

1 Time

1.1 The Shot & Scene

A shot is a series of uninterrupted frames. Several shots edited together forms one scene. Every scene is a coherent narrative with a beginning, middle and end.

1.2 Altering Time

- Slow Motion

- Fast Mostion

1.3 Accelerating & Freezing Time

- Time-lapse photography

- Frozen moments

2 Camera & Space

2.1 Camera Height

- Eye Level Shot

- High(er) Level

- Low(er) Level

2.2 Camera Angle

- High-Angle Shot

- Low-Angle Shot

- Dutch Angle Shot / Canted Shot

- Overhead Shot / Bird’s Eye View Shot

2.3 Camera Distance

- Extreme Long Shot (XLS)

- Long Shot (LS)

- Medium Long Shot (MLS)

- Medium Shot (MS)

- Medium Close-up (MCU)

- Close-up (CU)

- Extreme Close-up (XCU)

2.4 Camera Move: Exploring Space

- Horizontally (Panning)

- Vertically (Tilting)

- Tracking Shot

- Crane Shot

- Aerial Shot

- Handheld Shot & Steadicam

Tuesday, May 11, 2010

Composition

Composition is a very important part of a film's mise en scène

Composition is the “visual arrangement of the objects, actors, and space within the frame” (Prammaggiore & Wallis, 82). The term “composition” literally means “to put together,” and usually arranging things aesthetically according to the principles of art. The typical principles of art are dynamism (movement), harmony (unity), variety (alternation), balance, contrast, proportion, rhythm (pattern).

In the medium of film these principles manifest in the following elements:

Balance & Symmetry

“A balanced composition has an equitable distribution of bright and dark areas, striking colours, objects and / or figures” (Prammaggiore & Wallis, 82).

Lines & Diagonals

“The human eye tends to respond to diagonal lines, vertical lines, and horizontal lines in decreasing emphasis. All three may be used as compositional elements, but a diagonal line carries the most visual weight” (Prammaggiore & Wallis, 83).

Framing

Framing refers to the amount of open space between the figures (actors) and objects and the border of the shot. “Loose framing refers to shots in which figures have a great deal of open space around them—this may suggest freedom or isolation, depending upon the narrative context and other elements in the frame. Tight framing describes an image in which the lack of space around the subject contributes to a sense of constriction” (Prammaggiore & Wallis, 84).

Foreground & Background

Foreground refers to the objects or action that happens closest to the cameral; conversely, the background is the part of the frame furthest away from the camera. The camera focus on either the foreground or the background with different effects.

Light & Dark

“Arranging light and dark areas in the frame is an important aspect of composition and can contribute to balance” (Prammaggiore & Wallis, 86).”

Colour

Different colours can create different moods or meanings in a film. “Because viewers perceive reds, yellows, and oranges as warm (vibrant with energy), and blues and greens as cool (relaxing rather than exciting), filmmakers choose to incorporate colors into sets, costumes, and propos according to the effect they are seeking to create. Like any other visual technique, color in the mise en scène may function as a motif.”

Colours can be described according to their saturation—referring to the strength of the colour. If the colour is not very pure, if it looks pale or washed out, it is desaturated. Saturated colours could suggest energy and vibrancy, while desaturated scenes may suggest a downbeat atmosphere. It is important to take the symbolic / cultural value of colour into account. For instance black is often symbolically used for death or mourning, and white for purity or innocence. Filmmakers may attached their own meanings to colour which you may need to decipher from the context.

Composition is the “visual arrangement of the objects, actors, and space within the frame” (Prammaggiore & Wallis, 82). The term “composition” literally means “to put together,” and usually arranging things aesthetically according to the principles of art. The typical principles of art are dynamism (movement), harmony (unity), variety (alternation), balance, contrast, proportion, rhythm (pattern).

In the medium of film these principles manifest in the following elements:

Balance & Symmetry

“A balanced composition has an equitable distribution of bright and dark areas, striking colours, objects and / or figures” (Prammaggiore & Wallis, 82).

Lines & Diagonals

“The human eye tends to respond to diagonal lines, vertical lines, and horizontal lines in decreasing emphasis. All three may be used as compositional elements, but a diagonal line carries the most visual weight” (Prammaggiore & Wallis, 83).

Framing

Framing refers to the amount of open space between the figures (actors) and objects and the border of the shot. “Loose framing refers to shots in which figures have a great deal of open space around them—this may suggest freedom or isolation, depending upon the narrative context and other elements in the frame. Tight framing describes an image in which the lack of space around the subject contributes to a sense of constriction” (Prammaggiore & Wallis, 84).

Foreground & Background

Foreground refers to the objects or action that happens closest to the cameral; conversely, the background is the part of the frame furthest away from the camera. The camera focus on either the foreground or the background with different effects.

Light & Dark

“Arranging light and dark areas in the frame is an important aspect of composition and can contribute to balance” (Prammaggiore & Wallis, 86).”

Colour

Different colours can create different moods or meanings in a film. “Because viewers perceive reds, yellows, and oranges as warm (vibrant with energy), and blues and greens as cool (relaxing rather than exciting), filmmakers choose to incorporate colors into sets, costumes, and propos according to the effect they are seeking to create. Like any other visual technique, color in the mise en scène may function as a motif.”

Colours can be described according to their saturation—referring to the strength of the colour. If the colour is not very pure, if it looks pale or washed out, it is desaturated. Saturated colours could suggest energy and vibrancy, while desaturated scenes may suggest a downbeat atmosphere. It is important to take the symbolic / cultural value of colour into account. For instance black is often symbolically used for death or mourning, and white for purity or innocence. Filmmakers may attached their own meanings to colour which you may need to decipher from the context.

Tuesday, April 6, 2010

Mise en scène

The mise en scène concerns the look and feel of the set (i.e. the “stage” in which every scene is shot). It can be described as the arrangement and design of the scene. Everything you see in the frame contributes to the mise en scène: the setting, the human figure, lighting, and how it is all put together as one composition.

Filmsite.com defines mise en scène as: “a French term for "staging," or "putting into the scene or shot"; in film theory, it refers to all the elements placed (by the director) before the camera and within the frame of the film -- including their visual arrangement and composition; elements include settings, decor, props, actors, costumes, makeup, lighting, performances, and character movements and positioning; lengthy, un-cut, unedited and uninterrupted sequences shot in real-time are often cited as examples of mise-en-scene…”

Setting

The setting focuses on the location of the scene (i.e. the place where the action happens), which includes the landscape, architecture and the interior design. The setting also included décor and other objects—the additional props. The filmmaker may at times use natural settings, and at other times they may build custom made “constructed sets.” When a film is shot at a specific place—for instance the Korean drama Iris had scenes in Turkey—we refer to it as “shot on location.” The location they are depicting is Turkey, and the film was shot in Turkey, so it was “shot on location.” In more recent films blue / green screens are used onto which a CGI-background is superimposed. CGI is the abbreviation for computer generated imagery.

Pramaggiore & Wallis (60) highlights the value of setting in the following quote: “The visual characteristics of a setting evoke responses from the audience. Do events take place inside buildings or outside? Are settings living spaces, work places, or public places? Are they spacious or cramped, sunny and bright, or dim and shadowy? Are they full of bits and pieces or empty?”

Each one of these settings will create a different mood. Setting also establish the time and place in which the action occurs. More abstract information such as themes and motifs can also be conveyed through the setting.

The Human Figure

The actor, as primary agent, forms a very important part of the scene. Each actor has a different look and “feel” about them. Their appearance and acting styles will bring a unique quality to each scene. Add to this the costumes worn by the actors, the make-up used, as well as props placed in each scene, and you may get an idea of the value that a person brings to the scene.

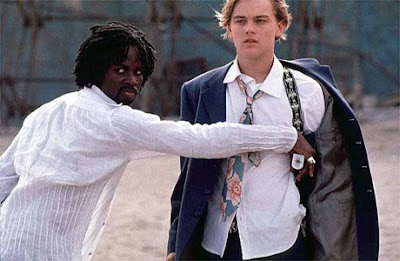

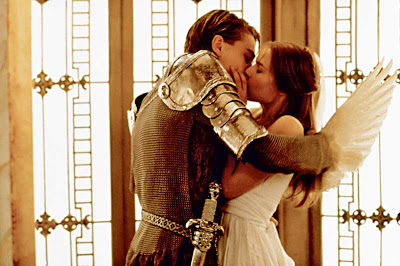

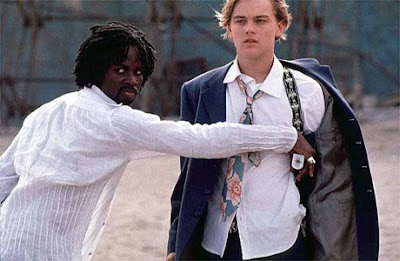

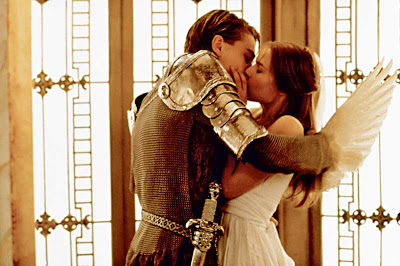

The character’s body can, in a way, become a “prop” too. In some scenes character’s are directed to position themselves in specific postures and placements within a shot, for specific dramatic effect. Look at the following pictures. What is the feeling or meaning conveyed? Especially consider the positioning of the actors’ bodies.

Lighting

Another element that contributes to the mise en scène is the lighting. Lighting can be described according to its quality (hard or soft), it’s placement (the direction from which it shines on objects), and the contrast it creates (high or low contrast).

Look at the following screen shots and consider the lighting’s quality, placement, and contrast. Why do you think the filmmakers chose that specific lighting? What are the moods that are achieved?

Composition

Composition is another important aspect of mise en scène which we will discuss later in more detail. In the meanwhile, thing of composition as the "balance" of each frame. Many things contribute to the composition, such as straight and diagonal lines, the foreground and background, the use of light and dark, as well as the artistic use of colour.

Filmsite.com defines mise en scène as: “a French term for "staging," or "putting into the scene or shot"; in film theory, it refers to all the elements placed (by the director) before the camera and within the frame of the film -- including their visual arrangement and composition; elements include settings, decor, props, actors, costumes, makeup, lighting, performances, and character movements and positioning; lengthy, un-cut, unedited and uninterrupted sequences shot in real-time are often cited as examples of mise-en-scene…”

Setting

The setting focuses on the location of the scene (i.e. the place where the action happens), which includes the landscape, architecture and the interior design. The setting also included décor and other objects—the additional props. The filmmaker may at times use natural settings, and at other times they may build custom made “constructed sets.” When a film is shot at a specific place—for instance the Korean drama Iris had scenes in Turkey—we refer to it as “shot on location.” The location they are depicting is Turkey, and the film was shot in Turkey, so it was “shot on location.” In more recent films blue / green screens are used onto which a CGI-background is superimposed. CGI is the abbreviation for computer generated imagery.

Pramaggiore & Wallis (60) highlights the value of setting in the following quote: “The visual characteristics of a setting evoke responses from the audience. Do events take place inside buildings or outside? Are settings living spaces, work places, or public places? Are they spacious or cramped, sunny and bright, or dim and shadowy? Are they full of bits and pieces or empty?”

Each one of these settings will create a different mood. Setting also establish the time and place in which the action occurs. More abstract information such as themes and motifs can also be conveyed through the setting.

The Human Figure

The actor, as primary agent, forms a very important part of the scene. Each actor has a different look and “feel” about them. Their appearance and acting styles will bring a unique quality to each scene. Add to this the costumes worn by the actors, the make-up used, as well as props placed in each scene, and you may get an idea of the value that a person brings to the scene.

The character’s body can, in a way, become a “prop” too. In some scenes character’s are directed to position themselves in specific postures and placements within a shot, for specific dramatic effect. Look at the following pictures. What is the feeling or meaning conveyed? Especially consider the positioning of the actors’ bodies.

Lighting

Another element that contributes to the mise en scène is the lighting. Lighting can be described according to its quality (hard or soft), it’s placement (the direction from which it shines on objects), and the contrast it creates (high or low contrast).

Look at the following screen shots and consider the lighting’s quality, placement, and contrast. Why do you think the filmmakers chose that specific lighting? What are the moods that are achieved?

Composition

Composition is another important aspect of mise en scène which we will discuss later in more detail. In the meanwhile, thing of composition as the "balance" of each frame. Many things contribute to the composition, such as straight and diagonal lines, the foreground and background, the use of light and dark, as well as the artistic use of colour.

Tuesday, March 30, 2010

Assignments: Narrative Structure & Postmodernism

Assignment: Narrative Structure

Describe the narrative structure of Shakespeare in Love (1998). Choose from the Three Act, Four Act, or Five Act (Dramatic) structure, the one you think most appropriate for this film then describe the basic plot of the film according to each act. Use the narrative structure terminology you have learned.

Assignment: Postmodernism

The time we are living in is known as Postmodernism. Therefore, the ideas and concepts associated with Postmodernism can often been seen in contemporary art, including contemporary films such as Romeo + Juliet (1996) and Shakespeare in Love (1998).

Write an essay in which you:

1. explain what Postmodernism is, and

2. describe in what ways the films Romeo + Juliet and Shakespeare in Love are postmodern.

Your essay is likely to have five paragraphs: (1) introductory paragraph; (2) explanation of Postmodernism; (3) discussion of Romeo + Juliet as a postmodern film; (4) discussion of Shakespeare in Love as a postmodern film; (5) conclusion. Remember to include references.

Wednesday, March 24, 2010

Narrative

Diegetic & Non-Diegetic Elements

Narrative films include elements that are part of the story-world, such as the setting, characters, and so on. This is collectively known as the diegesis. The elements that make up the diegesis are referred to as the diegetic elements or digetic devices. Elements that are not part of the actual story, for example the musical score or the opening and closing credits are non-diegetic elements / devices. They all, however, form part of the overall storytelling, i.e. the narrative. Therefore, narrative elements include both diegetic and non-diegetic elements.

Story (Fabula) and Plot (Syuzhet)

When we speak of “narrative” we usually mean “story.” A story is a series of events that are recounted (i.e. described or narrated) in their chronological order. However, if you know anything about stories, you will know that story events are not always told in chronological order. There is a difference between a narrative’s story (the chronological events, also known as the fabula) and its plot. The latter is the events of the story, which have been rearranged in a creative way to enhance the story. In the plot, also known as the syuzhet, the story events are not always in a chronological sequence. Past events may be shown (flashbacks) or future events (flashforwards) may be narrated early in the the story telling. Many well known narratives do not commence at the beginning of the story – some actually start at the end, for instance the films Citizen Kane (1941) and Momento (2001).

Narrative Structure

The narrative structure of a classical drama, like the Shakespearean play, can be depicted by the following illustration, known as Freytag’s pyramid.

Act One: The narrative starts with an exposition which provides the background information and introduces the characters (protagonists and antagonists), the setting and also the basic conflict and an inciting moment. The inciting moment is what causes the protagonist to act.

Act One: The narrative starts with an exposition which provides the background information and introduces the characters (protagonists and antagonists), the setting and also the basic conflict and an inciting moment. The inciting moment is what causes the protagonist to act.

Act Two: This leads to a rising action; the conflict becomes clearer as the story progresses.

Act Three: Eventually there is the climax. The climax is where a big change in the story occurs, also known as the turning point. Things will either go well or bad for the protagonist.

Act Four: Next is the action starts to wane (falling action) as the conflict between the protagonist and the antagonist unravels.

Act Five: Finally there is a resolution – a dénouement (happy conclusion) or a tragic ending.

The typical narrative film follows a similar structure, but instead of the five act structure it is condensed into only three acts. Act One contains the exposition and turning point. Act Two includes the complications that lead to the climax. Lastly, in the third act the action falls and the story comes to some resolution.

Another interpretation by Kristin Thompson is that contemporary narrative follows a four-act structure, rather than a three-act structure, in which the first act contains the exposition and a first turning point, in the second act the action leads up to the major turning point, in the third act the struggle continues toward the goal or climax, and finally in the fourth act the story comes to a resolution, known as the epilogue.

When describing the plot of a film it is useful to keep these narratives structures in mind to help you organize the narrative in a coherent manner.

While the three-act or four-act narrative structures are common, they are not the only narrative structures. To understand other types of narrative structures, we need to understand narrative layers.

Narrative Layers

A single narrative layer is one level at which the story occurs. However, it is possible to have another story occurring within the main story – for instance, the characters in the main story could be telling another story (maybe even reading a bedtime story), and so we have a story within a story. In other words, there are two diegesis or two layers, the one embedded in the other. In theory any amount of narrative layers are possible. The first narrative layer is often referred to as the “frame narration” in film theory.

Some Variation on Narrative Structure

Narrative structures usually have a clear and expected flow of events. A protagonist faces a problem (antagonist) or goal, strives to overcome or achieve it, a climax results after which the protagonist has overcome the problem or achieved the goal, or where the protagonist fails (in which case it is called a tragedy). But in the end, there is a resolution. In other words, the audience understands that the story has ended – there is closure. Traditional narratives are also clear, the audience easily understands the space, time, and events; there is also unity between the causes and effects; the characters are identifiable and their motivations understandable; and the focus is on the diegesis.

Some narratives are not so clearly defined. A number of narratives may seem to lack a clear problem or goal for the protagonist to overcome or achieve – these are called episodic narratives. Other narratives may be open ended, i.e. there is no resolution and the audience is left unsure whether the protagonist has achieved the goal, or overcome the problem – there may still be unanswered questions, or unresolved conflicts. The narrative may also depart from traditional conventions: it may lack clarity with conflicting storylines and space, time and events that are difficult to understand; there may be a lack of unity where the law of cause and effect is not upheld; characters’ goals and motivations are unclear, or they may be too far removed from “normal people” that the audience cannot identify with them; and there is an intrusive focus on the non-diegetic elements, like addressing the audience directly, or revealing cinematic “tools”, for instance showing the cameras.

Narration

In books it is much easier to identify the narrator, i.e. the person that is telling the story (i.e. the speaker). In literature there are also different words used to describe different types of narrations; for instance, it could be a first person narration (one of the characters is telling the story from his own point of few), a third-person narration (the story is not told by one of the characters), or in some cases even an omniscient narration (the narrator knows everything about everyone).

In film, it is much more difficult to identify the narrator. Usually there is no audible narrator – instead we only get to “see” what the cameras see. What the director (or cinematographer) chooses for us to see, is in effect part of the telling of the story – part of the narration of film. Sometimes the camera shows what one of the characters are seeing, as if we were seeing the world through the eyes of that character. This is known as a point-of-view shot, when the audience shares the visual perspective of a character. We will look at different ways of using the camera later in the course.

Apart from the camera giving us a visual interpretation of the diegetic world, there are also other narrative elements that contributes to the story telling, like sound, mise en scène, cinematography and editing. We already discussed sound and will discuss the other elements later.

Narrative films include elements that are part of the story-world, such as the setting, characters, and so on. This is collectively known as the diegesis. The elements that make up the diegesis are referred to as the diegetic elements or digetic devices. Elements that are not part of the actual story, for example the musical score or the opening and closing credits are non-diegetic elements / devices. They all, however, form part of the overall storytelling, i.e. the narrative. Therefore, narrative elements include both diegetic and non-diegetic elements.

Story (Fabula) and Plot (Syuzhet)

When we speak of “narrative” we usually mean “story.” A story is a series of events that are recounted (i.e. described or narrated) in their chronological order. However, if you know anything about stories, you will know that story events are not always told in chronological order. There is a difference between a narrative’s story (the chronological events, also known as the fabula) and its plot. The latter is the events of the story, which have been rearranged in a creative way to enhance the story. In the plot, also known as the syuzhet, the story events are not always in a chronological sequence. Past events may be shown (flashbacks) or future events (flashforwards) may be narrated early in the the story telling. Many well known narratives do not commence at the beginning of the story – some actually start at the end, for instance the films Citizen Kane (1941) and Momento (2001).

Narrative Structure

The narrative structure of a classical drama, like the Shakespearean play, can be depicted by the following illustration, known as Freytag’s pyramid.

Act One: The narrative starts with an exposition which provides the background information and introduces the characters (protagonists and antagonists), the setting and also the basic conflict and an inciting moment. The inciting moment is what causes the protagonist to act.

Act One: The narrative starts with an exposition which provides the background information and introduces the characters (protagonists and antagonists), the setting and also the basic conflict and an inciting moment. The inciting moment is what causes the protagonist to act.Act Two: This leads to a rising action; the conflict becomes clearer as the story progresses.

Act Three: Eventually there is the climax. The climax is where a big change in the story occurs, also known as the turning point. Things will either go well or bad for the protagonist.

Act Four: Next is the action starts to wane (falling action) as the conflict between the protagonist and the antagonist unravels.

Act Five: Finally there is a resolution – a dénouement (happy conclusion) or a tragic ending.

The typical narrative film follows a similar structure, but instead of the five act structure it is condensed into only three acts. Act One contains the exposition and turning point. Act Two includes the complications that lead to the climax. Lastly, in the third act the action falls and the story comes to some resolution.

Another interpretation by Kristin Thompson is that contemporary narrative follows a four-act structure, rather than a three-act structure, in which the first act contains the exposition and a first turning point, in the second act the action leads up to the major turning point, in the third act the struggle continues toward the goal or climax, and finally in the fourth act the story comes to a resolution, known as the epilogue.

When describing the plot of a film it is useful to keep these narratives structures in mind to help you organize the narrative in a coherent manner.

While the three-act or four-act narrative structures are common, they are not the only narrative structures. To understand other types of narrative structures, we need to understand narrative layers.

Narrative Layers

A single narrative layer is one level at which the story occurs. However, it is possible to have another story occurring within the main story – for instance, the characters in the main story could be telling another story (maybe even reading a bedtime story), and so we have a story within a story. In other words, there are two diegesis or two layers, the one embedded in the other. In theory any amount of narrative layers are possible. The first narrative layer is often referred to as the “frame narration” in film theory.

Some Variation on Narrative Structure

Narrative structures usually have a clear and expected flow of events. A protagonist faces a problem (antagonist) or goal, strives to overcome or achieve it, a climax results after which the protagonist has overcome the problem or achieved the goal, or where the protagonist fails (in which case it is called a tragedy). But in the end, there is a resolution. In other words, the audience understands that the story has ended – there is closure. Traditional narratives are also clear, the audience easily understands the space, time, and events; there is also unity between the causes and effects; the characters are identifiable and their motivations understandable; and the focus is on the diegesis.

Some narratives are not so clearly defined. A number of narratives may seem to lack a clear problem or goal for the protagonist to overcome or achieve – these are called episodic narratives. Other narratives may be open ended, i.e. there is no resolution and the audience is left unsure whether the protagonist has achieved the goal, or overcome the problem – there may still be unanswered questions, or unresolved conflicts. The narrative may also depart from traditional conventions: it may lack clarity with conflicting storylines and space, time and events that are difficult to understand; there may be a lack of unity where the law of cause and effect is not upheld; characters’ goals and motivations are unclear, or they may be too far removed from “normal people” that the audience cannot identify with them; and there is an intrusive focus on the non-diegetic elements, like addressing the audience directly, or revealing cinematic “tools”, for instance showing the cameras.

Narration

In books it is much easier to identify the narrator, i.e. the person that is telling the story (i.e. the speaker). In literature there are also different words used to describe different types of narrations; for instance, it could be a first person narration (one of the characters is telling the story from his own point of few), a third-person narration (the story is not told by one of the characters), or in some cases even an omniscient narration (the narrator knows everything about everyone).

In film, it is much more difficult to identify the narrator. Usually there is no audible narrator – instead we only get to “see” what the cameras see. What the director (or cinematographer) chooses for us to see, is in effect part of the telling of the story – part of the narration of film. Sometimes the camera shows what one of the characters are seeing, as if we were seeing the world through the eyes of that character. This is known as a point-of-view shot, when the audience shares the visual perspective of a character. We will look at different ways of using the camera later in the course.

Apart from the camera giving us a visual interpretation of the diegetic world, there are also other narrative elements that contributes to the story telling, like sound, mise en scène, cinematography and editing. We already discussed sound and will discuss the other elements later.

Labels:

fabula,

narration,

narrative,

narrative layers,

narrative structure,

plot,

story,

syuzhent

Sunday, March 14, 2010

Sound

Types of Film Sound

There are three types of film sound: dialogue, sound effects, and music.

Dialogue

The dialogue is the verbal narrative of the script, recited by the actors. A good actor will not merely repeat the words, but will bring meaning and life to it through the way he or she performs. To do this the actor uses pauses, intonation, emotion, voice volume, pitch, accent and dialect, and so on.

Under the dialogue heading we may also include the voice-over, where "someone" is speaking to the audience. The voice-over can be used to inform the audience of background information, inner-dialogue, and so one, which is often important for the coherence or comprehension of the narrative.

Sound Effects

Sound effects are an important component of a film’s sound because it contributes lots of important details to the film, and to the audience’s understanding of the scenes. [1] Sound effects can help the audience identify the location of the film – the sound of crickets could indicate a rural night scene, while the sound of traffic bustling by may suggest a city environment. [2] The sound also suggests certain moods to an environment. Horror movies, for instance, may employ “scary” noises to create a feeling of suspense and fear. [3] Sound effects can also indicate the environment’s impact on characters. A famous example is the “Crop Duster”-scene from Alfred Hitchcock’s North by Northwest (1959) where the audience can hear the plane coming closer and going further away, even though it is not always visible on the screen.

Sound effects have certain characteristics that you need to know about: acoustic qualities; volume; regularity; verisimilitude (sounding authentic).

Music

Music has an important function in film and contributes important meaning to the narrative. [1] The music may establish the historical context for the film. [2] The music also contributes to shaping the space and helps the audience establishes the space of the scene. [3] It also helps to shape the emotional tenor of the scene. A sinister melody may create a suspenseful mood, or a merry melody may create a corresponding cheerful mood. [4] Music can also contribute to defining character – well chosen music can become associated with certain characters, and so add to the characterization of that character. [5] The music could also “distance” the audience when the sound and the image contradict. Such well thought out juxtaposition of music and image by the filmmaker may give special meaning to the scene.

Music has five characteristics. Patterns of development (compare with motifs); lyrics; tempo & volume; instrumentation; cultural significane.

The Relationship between Sound and Image

The typical expectations are that the sound we hear should correspond with the image we see, and that the soundtrack should enhance the mood of the scene. When two actors speak to each other we expect to hear the dialogue, unless they are whispering; when a gun is fired we expect to hear the bang, unless it is fitted with a silencer, in which case we expect to hear a muffled shot. Also, when two lovers kiss we expect romantic music; conversely, in an action film sequence we expect fast paced music, or in a thriller there might be suspenseful sound effects.

However, the sound may differ from what we see and what we expect to hear. There are five ways in which the filmmaker can choose to create contrast; i.e. not conform to the audience's expectations. The five situations are contrasts in:

The soundtrack is often chosen to match the mood of different scenes in the film. However, a filmmaker may decide to use sound that seems inappropriate to the mood of the scene, in so doing creating supplementary meaning. The effect could be disturbing, humorous, ironic, etc.

There are three types of film sound: dialogue, sound effects, and music.

Dialogue

The dialogue is the verbal narrative of the script, recited by the actors. A good actor will not merely repeat the words, but will bring meaning and life to it through the way he or she performs. To do this the actor uses pauses, intonation, emotion, voice volume, pitch, accent and dialect, and so on.

Under the dialogue heading we may also include the voice-over, where "someone" is speaking to the audience. The voice-over can be used to inform the audience of background information, inner-dialogue, and so one, which is often important for the coherence or comprehension of the narrative.

Sound Effects

Sound effects are an important component of a film’s sound because it contributes lots of important details to the film, and to the audience’s understanding of the scenes. [1] Sound effects can help the audience identify the location of the film – the sound of crickets could indicate a rural night scene, while the sound of traffic bustling by may suggest a city environment. [2] The sound also suggests certain moods to an environment. Horror movies, for instance, may employ “scary” noises to create a feeling of suspense and fear. [3] Sound effects can also indicate the environment’s impact on characters. A famous example is the “Crop Duster”-scene from Alfred Hitchcock’s North by Northwest (1959) where the audience can hear the plane coming closer and going further away, even though it is not always visible on the screen.

Sound effects have certain characteristics that you need to know about: acoustic qualities; volume; regularity; verisimilitude (sounding authentic).

Music

Music has an important function in film and contributes important meaning to the narrative. [1] The music may establish the historical context for the film. [2] The music also contributes to shaping the space and helps the audience establishes the space of the scene. [3] It also helps to shape the emotional tenor of the scene. A sinister melody may create a suspenseful mood, or a merry melody may create a corresponding cheerful mood. [4] Music can also contribute to defining character – well chosen music can become associated with certain characters, and so add to the characterization of that character. [5] The music could also “distance” the audience when the sound and the image contradict. Such well thought out juxtaposition of music and image by the filmmaker may give special meaning to the scene.

Music has five characteristics. Patterns of development (compare with motifs); lyrics; tempo & volume; instrumentation; cultural significane.

The Relationship between Sound and Image

The typical expectations are that the sound we hear should correspond with the image we see, and that the soundtrack should enhance the mood of the scene. When two actors speak to each other we expect to hear the dialogue, unless they are whispering; when a gun is fired we expect to hear the bang, unless it is fitted with a silencer, in which case we expect to hear a muffled shot. Also, when two lovers kiss we expect romantic music; conversely, in an action film sequence we expect fast paced music, or in a thriller there might be suspenseful sound effects.

However, the sound may differ from what we see and what we expect to hear. There are five ways in which the filmmaker can choose to create contrast; i.e. not conform to the audience's expectations. The five situations are contrasts in:

- onscreen space and offscreen space

- objective images and subjective sound

- diegetic (story) details and non-diegetic (not part of the story) sound

- image time and sound time

- image mood and sound mood

The soundtrack is often chosen to match the mood of different scenes in the film. However, a filmmaker may decide to use sound that seems inappropriate to the mood of the scene, in so doing creating supplementary meaning. The effect could be disturbing, humorous, ironic, etc.

Sunday, March 7, 2010

Assignment

Some Cinematic Narrative Elements

Motifs

Sometimes in film certain detail is repeated and takes on special significance. Such repeated detail becomes a motif in the movie.

Parallels

When two or more characters, events, locations, situations, or other elements are compared or contrasted in a film, it is called a parallel.

Structure

It is always important to take special notice of a films structure. There may be parallels in the opening and closing scenes. The film’s narrative usually have important turning points. A director may indicate such turning points in the form of transitions which may include, for instance, a fade-out, or a change in the music.

Allusions

Allusions are “outside references” in a film that bring new meaning to the film.

The film may be placed within a specific historical setting or within a cultural attitude that causes the viewer to “read” the film in a special way. For instance, a story depicted during the Holocaust, e.g. Life is Beautiful (1997) , is read very differently from a film taking place on another planet, e.g. Avatar (2009). Both the historical setting and the cultural milieu in films supply the viewer with certain expectations and attitudes towards reading and understanding the film.

Stars (very famous actors) can also be a reference, often to certain genres. What type of movie comes to mind when Bruce Willis or Hugh Jackman is the leading actor? Most likely an action movie or suspense film. How about Hugh Grant? Probably a romantic-comedy. Jim Carrey? Comedy. And Johnny Depp? Probably a strange film with a quirky character.

When public figures or celebrities partake in a film they bring with them all kinds of associations. For instance, when Madonna acted in Evita (1996), many devotees of the real Evita Duarte de Peron of Argentina were outraged because Madonna’s reputation as the “Material Girl” contradicted with the virtuous ideas associate with Evita, the "spiritual leader" of Argentina.

Sometimes a movie may make references to other films or to other books or plays. This is known as an intertextual reference, and also contribute to the meaning of the film.

Summarized from Pramaggiore & Wallis, 2005. Film: A Critical Introduction. Laurence King Publishing.

Sometimes in film certain detail is repeated and takes on special significance. Such repeated detail becomes a motif in the movie.

Parallels

When two or more characters, events, locations, situations, or other elements are compared or contrasted in a film, it is called a parallel.

Structure

It is always important to take special notice of a films structure. There may be parallels in the opening and closing scenes. The film’s narrative usually have important turning points. A director may indicate such turning points in the form of transitions which may include, for instance, a fade-out, or a change in the music.

Allusions

Allusions are “outside references” in a film that bring new meaning to the film.

- Historical Setting & Cultural Attitudes

The film may be placed within a specific historical setting or within a cultural attitude that causes the viewer to “read” the film in a special way. For instance, a story depicted during the Holocaust, e.g. Life is Beautiful (1997) , is read very differently from a film taking place on another planet, e.g. Avatar (2009). Both the historical setting and the cultural milieu in films supply the viewer with certain expectations and attitudes towards reading and understanding the film.

- Stars as Reference

Stars (very famous actors) can also be a reference, often to certain genres. What type of movie comes to mind when Bruce Willis or Hugh Jackman is the leading actor? Most likely an action movie or suspense film. How about Hugh Grant? Probably a romantic-comedy. Jim Carrey? Comedy. And Johnny Depp? Probably a strange film with a quirky character.

- Public Figures & Celebrities

When public figures or celebrities partake in a film they bring with them all kinds of associations. For instance, when Madonna acted in Evita (1996), many devotees of the real Evita Duarte de Peron of Argentina were outraged because Madonna’s reputation as the “Material Girl” contradicted with the virtuous ideas associate with Evita, the "spiritual leader" of Argentina.

- Intertextual Reference

Sometimes a movie may make references to other films or to other books or plays. This is known as an intertextual reference, and also contribute to the meaning of the film.

Summarized from Pramaggiore & Wallis, 2005. Film: A Critical Introduction. Laurence King Publishing.

Labels:

allusions,

fade-out,

intertextual reference,

motifs,

music,

narrative,

parallels,

starts,

structure,

transitions,

turning-points,

Week 01

Metadata

When talking about movies it is often important to refer to the metadata. The metadata are all the important data concerning the production of the film and include the film title, film’s release date, the genre, as well as the names of all those involved, like the producer(s), director, writer(s), cinematographer, cast members, and so on.

Usually when writing an analysis of a movie you need not include all the metadata, merely the basic metadata, which include at least the title, release date, director, and main cast members. Other metadata can be mentioned as needed. For instance, if you discuss the special effects, you may need to supply the names of the chief special effects supervisor and/or chief computer graphics animator. Alternatively, if you discuss the mise-en-scène you may need to mention the names of the cinematographer and/or set designer.

A good website for finding the metadata of a film is the Internet Movie Database.

Usually when writing an analysis of a movie you need not include all the metadata, merely the basic metadata, which include at least the title, release date, director, and main cast members. Other metadata can be mentioned as needed. For instance, if you discuss the special effects, you may need to supply the names of the chief special effects supervisor and/or chief computer graphics animator. Alternatively, if you discuss the mise-en-scène you may need to mention the names of the cinematographer and/or set designer.

A good website for finding the metadata of a film is the Internet Movie Database.

Tuesday, March 2, 2010

Welcome to our class blog!

This blog functions as a platform for the dissemination of class notes and announcements. It is not, however, a substitute for your own notes taken during class. Please visit this website regularly for a summary of each class, some extra material, and announcements.

The purpose of this class is to consolidate your previous experience in literature with the visual arts, specifically film. This class will therefore serve a double purpose of introducing you to the fundamentals of Film Theory & Critique, using Shakespeare films as the vehicle. During this semester we will watch around thirteen movies that are either direct adaptations of Shakespeare plays, or roughly based on Shakespeare plays. Some of these plays you may have previously encountered while studying in the Department of English Studies.

Before we watch any new film, please ensure that you are familiar with the play it is based on. Try to read the play and, if possible, also an analysis. If time does not allow, please read a synopsis and analysis of the play – see the links to Shakespeare Resources on the side, or visit the Campus Library, or our department library (Room 305). There will be a quiz on each play before we watch the movie.

The first part of the semester (up until the Midterm Exam) will focus on the introduction of relevant Film Theory. The second part of the semester will focus more on discussions of the films using the theory you have learned, and preparation for your final exam submission. There will not be a final examination; instead you will submit a detailed film analysis of a selected film. A short list of films that you may write your analysis on will be given two weeks before the Final Exam week starts.

I look forward to watching great films with you!

The purpose of this class is to consolidate your previous experience in literature with the visual arts, specifically film. This class will therefore serve a double purpose of introducing you to the fundamentals of Film Theory & Critique, using Shakespeare films as the vehicle. During this semester we will watch around thirteen movies that are either direct adaptations of Shakespeare plays, or roughly based on Shakespeare plays. Some of these plays you may have previously encountered while studying in the Department of English Studies.

Before we watch any new film, please ensure that you are familiar with the play it is based on. Try to read the play and, if possible, also an analysis. If time does not allow, please read a synopsis and analysis of the play – see the links to Shakespeare Resources on the side, or visit the Campus Library, or our department library (Room 305). There will be a quiz on each play before we watch the movie.

The first part of the semester (up until the Midterm Exam) will focus on the introduction of relevant Film Theory. The second part of the semester will focus more on discussions of the films using the theory you have learned, and preparation for your final exam submission. There will not be a final examination; instead you will submit a detailed film analysis of a selected film. A short list of films that you may write your analysis on will be given two weeks before the Final Exam week starts.

I look forward to watching great films with you!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)